“Gentlemen,” the sheriff was saying, “it was on this very spot the day befoah the cholera broke out that I sole `im as a vagrant. An` I did (lie meanes` thing a man can evah do. I hel` `im up to public ridicule Ibh his weaknesses an` made spoht of `is infirmities. I laughed at `is povahty an` `is ole clo`es.

I delivahed on `im as complete an oration of sarcastic detraction as I could prepare on the spot, out of my own meanness an` with the vulgah sympathies of the crowd. Gentlemen, if I only had that crowd heah now, an` ole King Sol`mon standin` in the midst of it, that I might ask `im to accept a humble public apology, offahed liom the heaht of one who feels himself unworthy to shake `is han`! Hut, gentlemen, that crowd will nevah reassemble. Neahly ev`ry man of them is dead, an` ole King Sol`mon buried them.”

“He buried my friend Adolphe Xaupi,” said Francois Giron, touching his eyes with his handkerchief.

“There is a case of my best Jamaica rum for him whenever he comes for it,” said old Leuba, clearing his throat.

“But, gentlemen, while we are speakin` of ole King Sol`mon we ought not to fohget who it is that has suppohted `im. Yondah she sits on the sidewalk, sellin` `er apples an` gingerbread.”

The three men looked in the direction indicated.

“Heah comes ole King Sol`mon now,” exclaimed the sheriff.

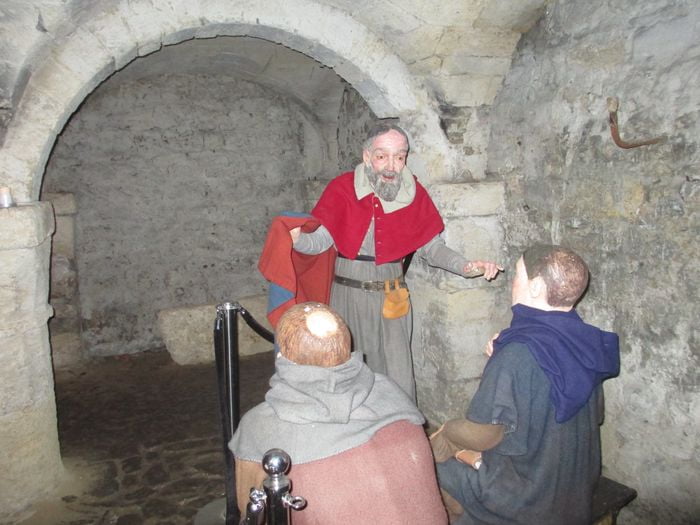

Across the open square the vagrant was seen walking slowly along with his habitual air of quiet, unobtrusive preoccupation. A minute more and he had come over and passed into the courthouse by a side door.

“Is Mr. Clay to be in court to-day?”

“He is expected, I think.”

“Then let`s go in; there will be a crowd.”

“I don`t know; so many are dead.”

Overwhelming Disaster

They turned and entered and found seats quietly as possible; for a strange and sorrowful hush brooded over the court room. Until the bar assembled, it had not been realized how many were gone. The silence was that of a common overwhelming disaster.

No one spoke with his neighbor, no one observed the vagrant as he entered and made his way to a seat on one of the meanest benches, a little apart from the others. He had not sat there since the day of his indictment for vagrancy.

The judge took his seat and, making a great effort to control himself, passed his eyes slowly over the court room. All at once he caught sight of old King Solomon sitting against the wall in an obscure corner; and before any one could know what he was doing, he hurried down and walked up to the vagrant and grasped his hand. He tried to speak, but could not. Old King Solomon had buried his wife and daughter buried them one clouded midnight, with no one present but himself.

Then the oldest member of the bar started up and followed the example; and then the other members, rising by a common impulse, filed slowly back and one by one wrung that hard and powerful hand. After them came the other persons in the court room.

The vagrant, the grave-digger, had risen and stood against the wall, at first with a white face and a dazed expression, not knowing what it meant; afterwards, when he understood it, his head dropped suddenly forward and his tears fell thick and hot upon the hands that he could not see. And his were not the only tears. Not a man in the long file but paid his tribute of emotion as he stepped forward to honor that image of sadly eclipsed but still effulgent humanity.

It was not grief, it was not gratitude, nor any sense of making reparation for the past. It was the softening influence of an act of heroism, which makes every man feel himself a brother hand in hand with every other- such power has a single act of moral greatness to reverse the relations of men, lifting up one, and bringing all others to do him homage.

It was the coronation scene in the life of old King Solomon of Kentucky.

Read More about King Solomon of Kentucky part 5